of Parks on Property Values

75% of The Premium Value

Generally Occurs Within The

500 to 600 Foot Zone

The Proximate Principle

The proximate principle states that the market value of properties located proximate to a park or open space are frequently higher that comparable properties located elsewhere.*

The increased capabliltiy of computing has made feasible more complex analyses enabling the economic contribution of parks/open space to property values to be quantitatively identified and distinguished from those attributable to other possible contributions.*

Peer Reviewed Studies

" Approximatley 20 studies investigating the issue have appeared in the past two decades. Most of the result have been published in peer reviewed journals which suggest they meet the standards of good social science research" *

They demonstrated that the proximate effect is substantial up to 800 - 600 feet ( typically three blocks).*

75% of the premium value generally occurs within the 500 - 600 foot zone.*

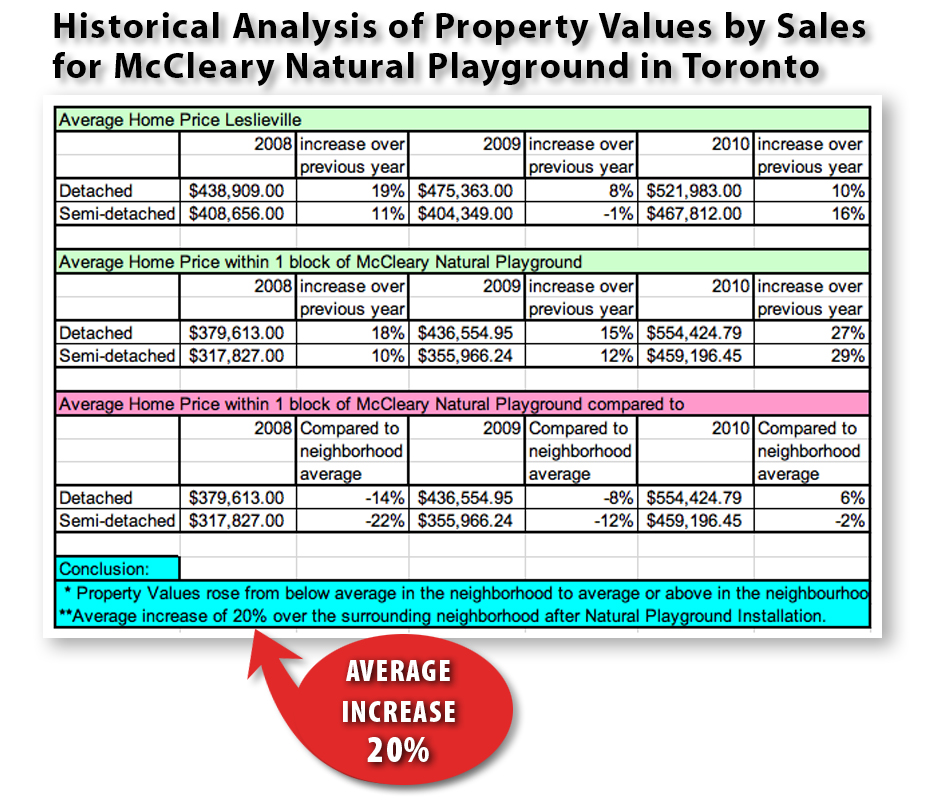

The studies suggested that a positive impact of 20% on properties abutting or fronting a passive park area as a reasonable point of departure for estimating the magnitude of the impact of parks on property values *

A series of studies done in New York City reported similar positive impacts emereged when substantial capital investment was made in renovating existing parks, which had deteriorated ( Ernst & Young 2003 )*

Property Value & Parks

A study conducted in 1995 by American Lives, Inc. reported that 77.7% of the study participants rated natural open space as "essential" or "very important" in planned communities.

Correll, Lillydahl, and Singell in 1978 estimated that the average value of a property adjacent to the greenbelt would be 32% higher than that of a similar property 3,200 feet away.

The effect of proximity to a park on residential values in Columbus, Ohio, found that homes that faced the park sold at a price 7% to 23% higher than the price at which similar residential properties just one block away were sold (Weicher and Zerbst, 1973).

2005, by Economic Research Associates, on behalf of the Illinois Association of Park Districts, concluded that neighborhood and community parks can have a significant effect on the values of nearby properties. In particular, based on the review of relevant studies, analysts indicate that homes facing neighborhood parks may register price increases up to a 20%, while homes facing community parks may register price increases up to 33%. Property-value benefits seem to extend 600 feet, in the case of neighborhood parks, and 2,000 feet, in the case of community parks.

Title: Real Estate Investing for Double-Digit Returns Authors: Petros S. Sivitanides,

Publisher: Booksurge Llc, 2008

ISBN1439213860, 9781439213865

The Price of Community Parks

Built Recently By Other Developers

In 2011 seven new parks opened in Toronto. All were built by developers.

The majority are simple green spaces with some children’s play equipment and typically cost between $800,000 and $1.2 million.

Departing from the cookie cutter approach that developers have taken in the past - a green space with a slide and that’s all, one developer decided that his park wouldn't be "just a place to walk your dog."

“We’re incorporating the park as a gathering place for the community.”

The final price tag will well exceed $2 million ....

Source: Sunday In The Park

by Robyn Doolittle Toronto Star 2012

Read Full Article: SundayInThePark

*References

Correll, Mark R., Lillydahl, J., Jane H. and Singell, Larry D. (1978). The effect of green belts on residential property values: Some findings on the political economy of open space. Land Economics 54(2), 207-217.

Crompton, John L. (2004). The proximate principle: The impact of parks, open space and waterfeatures on residential property values and the property tax base. Ashburn, Virginia: National Recreation and Park Association.

Ernest & Young (2003). Analysis of secondary economic impacts of New York city parks. New York City: New Yorkers for Parks.

Lutzenhiser, Margot and Netusil Noelwahr (2001). The effect of open spaces on a home’s sale price. Contemporary Economic Policy 19(3), 291-298.

Miller, Andrew R. (2001). Valuing open space: Land economics and neighborhood parks. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Real Estate.

Mulvihill, David A., et al. (2001). Golf course development in residential communities. Washington, DC: ULI-The Urban Land Institute.

Nicholls, Sarah and Crompton, John L. (2005a). Why do people choose to live in golf course communities? Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 23(1), 37-52.

Nicholls, Sarah and Crompton, John L. (2005b). The impact of greenways on property values: Evidence from Austin, Texas. Journal of Leisure Research 37(3), 321-341.

Nolen, John (1913). Some examples of the influence of public parks in increasing city land values. Landscape Architecture 3(4), 166-175.

Olmsted, Frederick Law, Jr. (1919). Planned residential subdivisions. Proceedings of the Eleventh National Conference on City Planning. Harvard University Press: 14-15